Understanding and encouraging financial inclusion is a major consideration not only for policymakers worldwide, but also for investors. Financial inclusion can boost productive investment and consumption, enabling economies to better manage risks and sustain future financial shocks. Observing the financial inclusion scores of different markets, we believe there are four distinct categories into which the 42 markets analyzed can be segmented. These categorizations provide an indication of some of the short-, medium-, and long-term risks to which economies are exposed.

1. Mature, forward-looking economies

The first category comprises markets which are both older, wealthy economies and exhibit actions related to financial inclusion—and other societal factors more broadly—which support long-term economic growth and resilience through business cycle peaks and troughs. Smaller Northern European economies are good examples.

The four Nordic markets analyzed—Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Norway—all rank in the top 10 for overall financial inclusion. This is largely driven by strong performances in government support, with all four ranking in the top six under this pillar. Sweden, Finland, and Denmark also rank in the top 10 in the financial system pillar, with Norway placing 12th.

Although the Nordics demonstrate the same inverse relationship as other markets (whereby higher scores in the government and financial system pillars are usually paired with lower scores in the employer pillar), their rankings for employer support are notably higher than the other larger European economies, such as the United Kingdom, France, and Germany.

These Northern European economies have constructed stable government systems, while their tried-and-tested financial infrastructure has evolved and strengthened through multiple economic cycles. This economic maturity is married with consideration of—and investment into—productivity requirements for the next 50 to 100 years.

These markets have been built on well-developed banking systems, which facilitate easy access to bank accounts and credit, by ensuring the financial infrastructure is tech-enabled and fit for purpose in a modern, digitized economy. These markets are considered some of the most technologically advanced nations in the world. Their scores for volume of real time transactions and presence, and quality of fintechs are generally strong and compare favorably with other major European markets.

The support offered at a state, employer, and financial system level in the Nordics is reflected in other aspects of their society. All four economies rank in the top 10 in the 2022 World Happiness Report and in the top 20 against indices tracking productivity. Equally, indices which measure an economy’s vulnerability to disruptive events and its ability to recover swiftly place three out of four of these markets in the top 10, with Finland just outside at 12th. These markets occupy four out of the top five spots in the Notre Dame GAIN Index, which summarizes an economy’s vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges in combination with its readiness to improve resilience.

Comparative indices rankings

| Market | Global financial inclusion | Food security | Happiness | Productivity | Economic resilience | Climate change adaptation | Human development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 3 | 12 | 20 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 19 |

| Finland | 5 | 3 | 1 | 15 | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Denmark | 6 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 9 |

| Norway | 9 | 17 | 40 | 38 | 42 | 1 | 41 |

Mature, forward-looking economies combine solid support across all three pillars of financial inclusion with strong performances in areas which are long-term risk factors, such as tech adoption, susceptibility to the effects of climate change, and the ability to maximize the potential of the workforce. By investing in these pillars, these markets are well equipped to not only withstand the challenges of the various megatrends facing society over the coming decades but to thrive in spite of them.

2. Mature, backward-looking economies

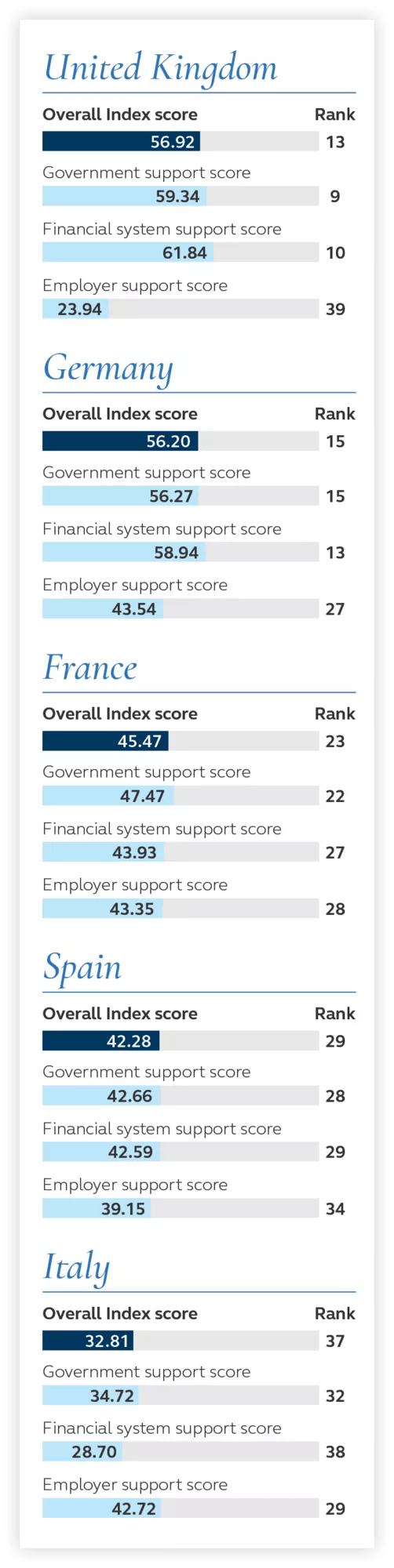

By contrast, the Global Financial inclusion Index suggests that Europe’s largest, oldest economies have not sufficiently invested in businesses and technology to futureproof financial inclusion for their own populations.

The U.K., Germany, Italy, France, and Spain receive underwhelming scores across the three pillars of financial inclusion. None of these economies feature in the top 10 overall; the U.K. ranks 13th, Germany 15th, France 23rd, Spain 29th, and Italy is a particular outlier at 37th.

Europe’s larger, older economies are wealthy nations which means that some of the cracks in the system and their failings in relation to financial inclusion are partially papered over. However, we believe that the actions of their governments, financial systems, and employers offer insights into significant long-term risks facing their economies.

Mediocre scores in the government and financial system support pillars are combined with universally low scores in the employer support pillar. This suggests that Europe’s older economies are becoming overly reliant on their government and financial support structures.

Four of the five markets land in the top half of the rankings for the state of public pensions, excluding Italy. However, when considering employee pension contributions, they drop much lower in the rankings with Germany ranking the highest at 17th out of 42. This reliance on public pensions versus individual contributions means as the aging population grows, so does the burden on the state. Over time, this becomes less sustainable without increased contributions from employers and workers. As populations age, the burden on the state increases and relying on government-provided pensions becomes less sustainable without increased contributions from employers and employees.

Not only does the data indicate that employer-sponsored pension systems are behind the curve in Europe’s major markets, but it also suggests that education and understanding around long-term savings is low. Scores for awareness and uptake of government-mandated pensions and savings are, with the exception of Italy, fairly weak, and all five markets rank in the bottom half of the table for availability of government-provided financial education.

Government support pillar

| Market | State of public pensions rank | Awareness and uptake of government-mandated pensions rank | Availability of government-provided financial education rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 18 | 19 | 38 |

| Germany | 13 | 30 | 39 |

| Italy | 31 | 9 | 27 |

| Spain | 21 | 37 | 36 |

| United Kingdom | 8 | 18 | 41 |

Employer support pillar

| Market | Employee pension/retirement contributions rank | Provision of guidance and support around financial issues rank |

|---|---|---|

| France | 27 | 31 |

| Germany | 17 | 35 |

| Italy | 32 | 29 |

| Spain | 35 | 32 |

| United Kingdom | 21 | 39 |

By failing to engage their aging populations around the threats of inadequate retirement income—neither at an employer nor government level—many of the continent’s largest markets could be facing a potential pension crisis. The relatively generous level of state pension provision and comparatively high degree of household wealth means that this issue does not result directly in economic pressure today, but unfortunately may encourage complacency and poses a serious long-term risk to economic health and resilience over the next several decades.

Within France, Germany, Italy, and Spain in particular, this has the potential to create financial strains within the European Union and could become a source of regional destabilization. To combat this headwind, adapting current systems to align with the Nordic pension model or even a hybrid model with some aspects borrowed from the Nordics or the United States, could improve retirement outcomes and drive greater financial inclusion.

Conversely, a long-term risk factor Europe does appear better positioned to manage than many other global markets is its exposure to the threats of climate change. Like pensions, environmental risks are much longer term in nature. Europe’s largest five economies all rank in the top quartile for their capacity to improve resilience to climate change, as measured by the Notre Dame GAIN Index.18

The long-term investment prospects for the mature, backward-looking economies are clouded by risk—in particular, risk linked to failing to modernize a long-term savings culture that keeps pace with aging demographics. While these economies attract significant global investment today due to their maturity, wealth, and ample capital markets, it's important they invest more in the financial futures of their populations to remain attractive for the long-term.

3. Young, forward-looking economies

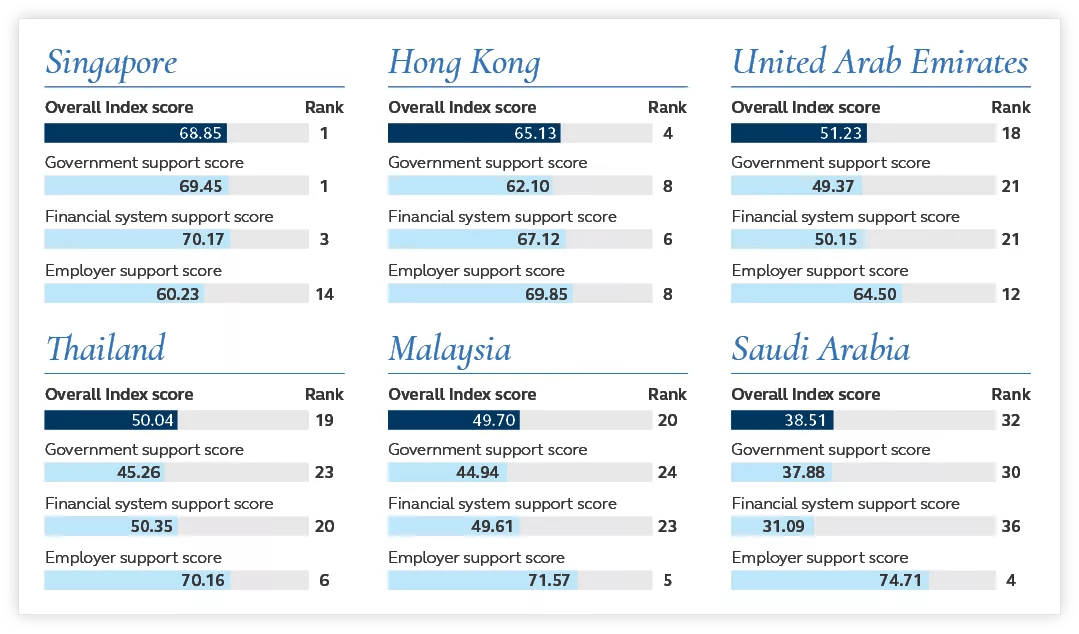

While the highest ranked markets for financial inclusion overall include many Northern European nations, the data shows that several newer economies, particularly in Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, are investing in initiatives now which could make a significant difference to financial inclusion, as well as growth and economic resilience, in the future. Notably, Singapore ranks first overall, and Hong Kong ranks fourth, but an analysis of the underlying data reveals further trends of note.

Comparatively young economies, such as Singapore, Hong Kong, the United Arab Emirates, Thailand, Malaysia, and Saudi Arabia score, on average, quite favorably on indicators such as employer guidance, pensions and insurance, financial technology and digital infrastructure, consumer protection, and government sponsored financial education.

Notably, some of the “young” markets which rank highly on the above indicators also rank in the bottom 10 for financial literacy levels and for overall education levels. With the exceptions of Singapore and Hong Kong, these markets rank in the bottom half of the table for both indicators.

In other words, in young economies where financial literacy is relatively low, but where the middle class is growing, governments, financial systems, and employers are working effectively in collaboration, investing in forward-looking initiatives which will help their populations manage their increasing wealth and ensure that this is distributed back into the economy to stimulate growth.

Newer economies have dynamic governments and private sectors; they are often purpose-built and have taken the most financially inclusive aspects of other markets to shape their society. The wealthier among them (such as Singapore and Hong Kong) can cherry-pick the infrastructure, regulation, and the structure of their financial systems around the growing wealth of their populations, with a view to creating the leading global economies of the next 100 years.

Technology and online connectivity are key components of success, enabling these markets and their citizens to benefit economically from globalization. What took hundreds of years to achieve in older markets, newer economies are managing in fractions of the time. Hong Kong, the UAE, Thailand, and Singapore all rank in the top 10 for online connectivity, and Singapore and Thailand appear in the top 10 for real time payments. Singapore ranks fourth and Hong Kong 13th for the presence and quality of fintechs indicator. Digital finance is equipping people to smooth their consumption, allowing them to save for rainy days and invest in their businesses, pushing income potentials higher.

New, forward-looking economies, which are investing in financial inclusion now, have huge long-term growth potential. However, in the near-term, when faced with the prospect of a global downturn, they are potentially more exposed to volatility given their financial systems have not been stress-tested through multiple economic cycles in the same way as more mature markets.

| Overall index score | Government support score | Financial system support score | Employer support score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore | 68.85 | 69.45 | 70.17 | 60.23 |

| Hong Kong | 65.13 | 62.10 | 67.12 | 69.85 |

| United Arab Emirates | 51.23 | 49.37 | 50.15 | 64.50 |

| Thailand | 50.04 | 45.26 | 50.35 | 70.16 |

| Malaysia | 49.70 | 44.94 | 49.61 | 71.57 |

| Saudia Arabia | 38.51 | 37.88 | 31.09 | 74.71 |

4. Reliant economies

The fourth category comprises markets which, to date, have lacked the resources to invest in the financial and social systems—including those promoting financial inclusion—which contribute to economic resilience and growth. The economies which score poorly for financial inclusion are predominantly developing markets situated in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa.

In these regions, scores for education levels and financial literacy are very low, as are the scores for online connectivity and key factors relating to the financial system, such as access to bank accounts and credit. In short, economic weakness has resulted in a limited ability to invest in the foundations for stability and growth. The majority of the markets toward the foot of the rankings for financial inclusion are heavily reliant on overseas aid and support from the International Monetary Fund.

Newer, forward-looking economies in Asia and the Middle East are illustrations that at the point in time when investments in financial and social systems become possible, economic development can be rapid. In a digitized global economy, relatively modest investments in businesses, technology, and financial infrastructure can have very significant and quick impacts, meaning J-curve growth versus the slow incline of the more mature markets.

But many of the markets in Latin America and Africa do not currently have the public or private sector capital to achieve this on their own. The decision by richer nations to provide financial support for poorer regions to invest in the building blocks of a more resilient economy is not only a moral choice but enlightened self-interest. Globalization, complex supply chains, and mobile populations mean that a failure to significantly improve financial conditions in struggling economies can have dramatic effects in developed markets.

For example, while several studies have argued the longer-term benefits of introducing younger, migrant workers to a market, the influx of refugees into Germany following the Syrian war had a destabilizing short-term impact.19 By supporting and investing in financial inclusion in markets facing severe social and economic challenges, richer nations can reduce poverty and spur greater economic growth, thereby reducing struggling nations’ migration needs.

In a globalized economy, long-term growth—and many of the financial and social factors which underpin it, such as financial inclusion—is not achieved on a purely national basis. Major threats in one market have the potential to pose significant risks to others. For the foreseeable future, any economy is only as strong as its neighbors.

World’s largest economies among outliers

There are a number of large economies that stand apart from these four categorizations. The financial inclusion scores of the U.S., China, and India do not comfortably fit into a box of mature or new, forward or backward-looking economies.

The U.S., for example, achieves scores comparable to a mature, backward-looking economy in terms of its government infrastructure but performs more like a young, forward-looking economy in terms of its tech adoption and pro-business philosophy. Its overall score is pulled down by its rankings for the complexity of corporate tax system and state of public pensions—broadly in keeping with the performance of continental Europe.

By contrast, the U.S. shares high rankings with new, forward-looking economies on indicators promoting business growth, technology, and employer support. The volume of real time payments indicator is weighted for population so even the United States' comparatively low rank of 25th should be read in the context of the large untapped market opportunity once a greater share of the population is using online banking. The U.S. has embraced digital innovation and online connectivity—and invested accordingly in the sector as a growth area—whilst empowering and incentivizing employers to create a stronger, more resilient economy.

China also defies categorization. It performs strongly against metrics which indicate that it should be well positioned to grow, including ranking in the top three for its financial system enabling business confidence, and just outside the top 10 for the presence and quality of fintechs. However, across its vast population, financial literacy and access to credit are low, creating barriers to productivity.

India ranks in the top 10 across all indicators under the employer support pillar, ranking first for provision of guidance and support around financial issues. It also scores highly on consumer championing regulation and availability of government-provided financial education. However, it places in the bottom two for online connectivity and financial literacy. As evidenced by the new, forward-looking economies, small investments into financial and social systems in India could have rapid impacts on both financial inclusion and broader economic development, which would position the economy well for future resilience and growth.

Gain more insights from the Global Financial Inclusion Index.

| Overall index score | Government support score | Financial system support score | Employer support score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 65.44 | 65.29 | 68.91 | 50.52 |

| Finland | 64.66 | 66.91 | 62.42 | 64.62 |

| Denmark | 63.87 | 65.01 | 64.31 | 56.77 |

| Norway | 63.08 | 66.19 | 59.44 | 65.49 |

| Overall index score | Government support score | Financial system support score | Employer support score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 56.92 | 59.34 | 61.84 | 23.94 |

| Germany | 56.20 | 56.27 | 58.94 | 43.54 |

| France | 45.47 | 47.47 | 43.93 | 43.35 |

| Spain | 42.28 | 42.66 | 42.59 | 39.15 |

| Italy | 32.81 | 34.72 | 28.70 | 42.72 |